Bookbinding

I am writing this down in the hope that it helps others, I have long wanted to learn bookbinding but it seemed a dark art surrounded in mystery, so over the last year or more I have been looking into it and the darkness has turned to light . . .

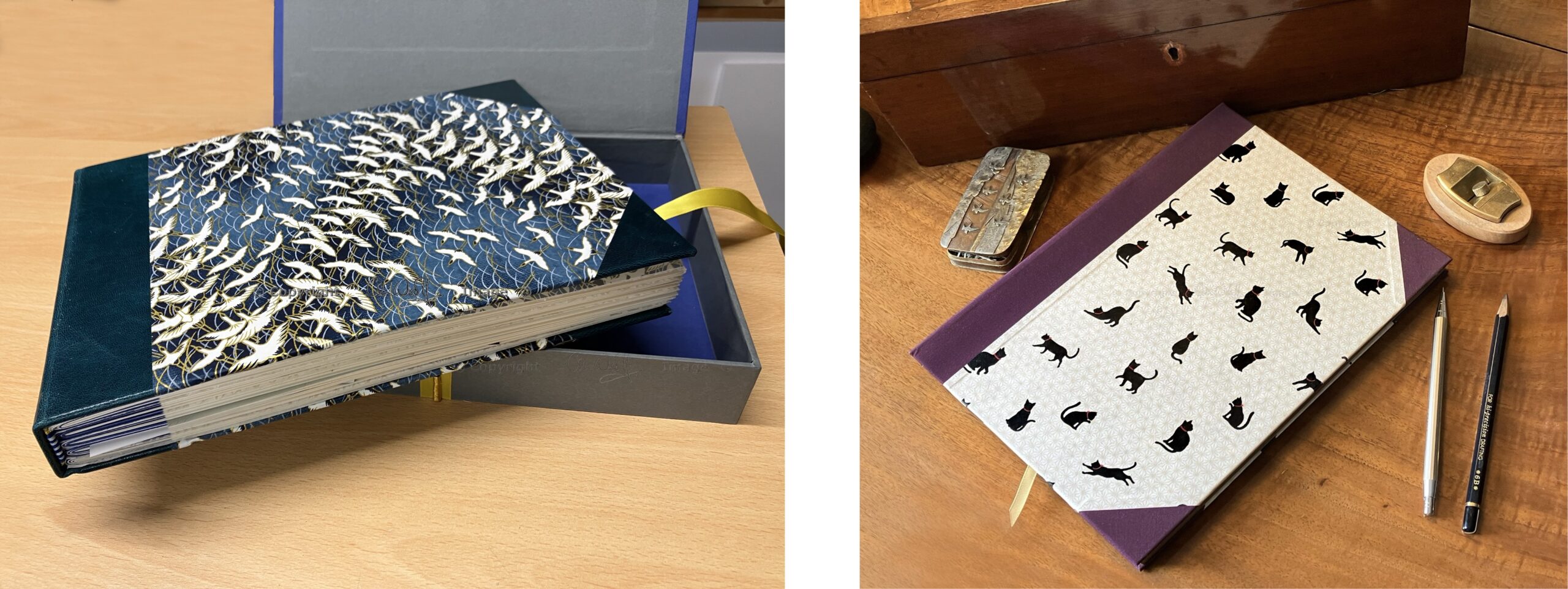

I have always been interested in the way books are made, whether they are the old leather-bound volumes like the Book of Kells or a modern hardback. Having commissioned a few leather-bound editions of our own books, I was keen to learn more. Whilst these special editions were being made (above) I watched the process and asked questions of the ‘master’ at work. He has since retired and sadly that company is no longer in production, so the need to learn the technique was heightened! I bought a few books on ‘how to’ and scoured the internet, but I am not good at learning from books and they seemed very scant in exactly how the process is completed.

I realised I'd have to get practical experience if I was to learn how it was done. My first project happened quite by accident, when I produced a book of memories for a special birthday (below left). I decided to make this from scratch, stitching the signatures (folded sections of pages) together and binding it with leather - a steep learning curve.

In bookbinding, it's important to have a thorough knowledge of the materials that you're using - what they're made of, what they do and how they affect the other components of the book. Tiny details can affect the finished look, so it's crucial to approach each task with time and care.

Thread

Traditional thread for book binding was made of linen. Irish linen was famous for this, but no company in Ireland is making it any more. I came across a wonderful French company called Fils au Chinois, but the supply of their products seemed erratic and expensive. Because I'd decided to use pure silk, this meant buying the right thickness and then comparing it to the linen thread normally used.

Fortunately, I found a great British supplier who winds the silk specifically for you and they were most helpful in supplying a thicker thread than their normal one, which I wanted to bind my books. I ordered some and put it on my chart so that I can see the diameter in comparison to other book-binding threads.

Japanese silk is a little more readily available but again the sizes are difficult to get and they are mostly very fine or made in a thick embroidery style with at least 6-ply which is much looser than typical sewing thread (see the red thread on the right in the image below).

Below: linen threads on the left and silks on the right

(A detailed look at threads and sizes can be found at the bottom of the page)

Conservation quality

When you pick up a really old book (for example, an old Bible), you may well notice the quality and cleanness of the paper. When compared with modern, mass-produced books, the difference is obvious - these will yellow over time and the paper will deteriorate.

I want to ensure that my books will last into the future and maybe attempt some conservation work too. The materials chosen all have to be of at least conservation or archive/museum quality, to ensure that the book lasts and does not affect the inside pages in a bad way.

Using the wrong glue, for example, will cause problems further down the line if anyone needs to remove the cover at a later stage. All the glues I use are reversible with water. The ones used in the really old books were the same as we use today.

Paper, board, glue, leather, etc can be sourced fairly easily once you've found out which ones are archive quality. This makes the choice much simpler.

Paper

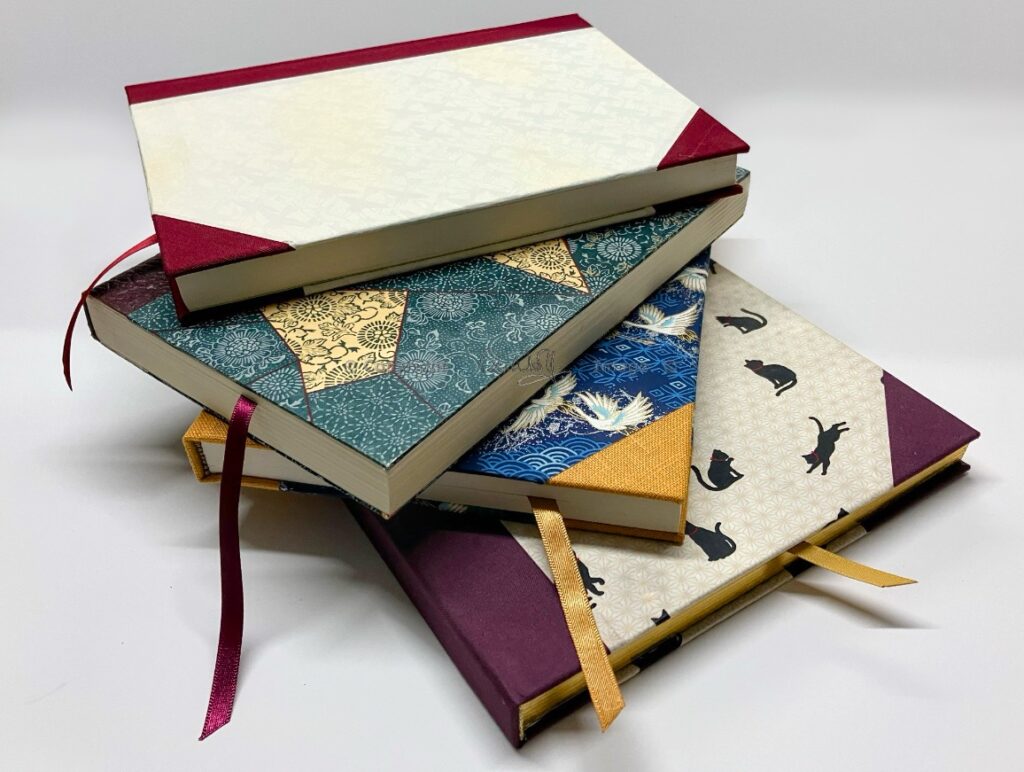

I'm a great fan of Japanese and Chinese art and culture, so it was natural that these papers featured in my work.

Chiyogami (literally a ‘thousand different papers’) or Yuzen paper is a traditional Japanese paper inspired by Edo-period kimono patterns. These vibrant, colourful, nature-inspired designs are silk-screened by hand onto durable Washi paper made from kozo/mulberry fibres.

They are beautiful but also expensive: sometimes I can only get one set of endpapers for a book out of one sheet. Luckily I found a printing house in Japan that has been in the same family for generations and still makes this wonderful paper by hand (and their designer still designs Kimono patterns). From conversations with a family member, I learned that it's becoming increasingly difficult to keep the production process going, due to rising costs and decreasing demand - and of course the flood of cheap and inferior digitally-printed copies, which do not have the same feel or look as the genuine article.

We agreed on a consignment of papers and I was even asked to assist in the making of a new design of paper never printed before. I'm very excited to see the results!

Leather

This is by far the most expensive element in bookbinding. A single small skin can cost anything upwards of £75. There are so many different types and tanning processes that choosing leather is a bit of a minefield, and caution is needed as some of the processes use toxic chemicals.

A bookbinder needs to learn the skill of paring leather with a sharp knife to reduce its thickness, which will allow it to be turned over edges without adding too much bulk. This is a taxing process that cannot be rushed. I was fortunate to have a short lesson from the master craftsman who made our special books for the Woodcock edition.

I like the effect of half-leather binding, where the spine and the corners are protected, so most of my bindings will be in this style.

Assembling the book

I decided that the best and quickest way to learn would be to take an existing book, remove the cover and re-bind the insides using my own design and choice of cover materials.

A clean workspace is essential, as any small specks of fabric or paper can get caught up in the glueing process and cause problems.

Learning these skills also gave me an insight into the conservation process involved in repairing a damaged book - because first of all you need to remove the damaged cover from the contents, but in doing so you have to be extremely careful not to damage the insides!

PRESSING

To ensure that a book or a cover stays flat, it is necessary to put them into a book press while they dry. There are some lovely antique presses available, but I decided to make my own. I wanted to make it attractive as well as functional.

I love all kinds of wood, and some of the pieces I've collected over the years have moved house with me about ten times! To make my press, I selected a lovely piece of oak. It has to be said that I'm am no woodworker - in fact, I've never made a wood joint in my life - so there was a lot of learning to do.

I'm very proud of the finished press, and it has been used very many times already.

The process of binding a book is very straightforward but needs care and attention to small details - something the monks of old were very good at.

My Bookbinding press

Each book is unique and totally individual. Like all handmade things, they each have their little idiosyncrasies. Each one is embossed with a special seal and is accompanied by a hand-written list of the specific materials used to make it.

Books can be made up to your individual specification

Threads explained

The most frustrating part of the whole process was trying to find out what thickness of thread to use for the stitching of the signatures. There seems to be no information about diameters of thread at all: I was just advised to use a 16/3 or 18/3 linen thread which is a weight and ply measurement. I wanted to use silk, so I needed some idea of how thick the silk should be. For threading a needle or passing it through a bead, you need to know its thickness or diameter. However, all threads are measured by weight, because they were originally sold in bulk - how many hanks of cotton (840 yards) weighs 1 pound, the Denier system is the weight of 9000m of thread, so 100D means 9000m weighs 100g.

This is all good, but it doesn't tell you how thick the thread is! One of the most popular makers, Gutermann, numbers their threads on a scale of thickness - rather confusingly, the higher the number, the thinner the thread.

After exhaustive research I could find no information on how to compare the thicknesses of different makes of thread - only unhelpful charts entitled 'thread sizes compared' which didn't specify diameters. I realised I'd have to work it out myself. I laid out threads and put them in order of thickness. For some, I was able to source actual diameters and for others there was a reference to a known system (Denier, TEX, Guntz etc). This enabled me to put them in some order. It became apparent that one manufacturer's idea of a measurement is not the same as another’s, so it's necessary to approach this question from another angle. This chart is constantly evolving as I find out new information: see image >.